A Contest of Wills

“No worries m’Love, I got this.” I said to Roni with studied nonchalance, standing in our front yard on a beautiful spring day and looking forward to doing something with my hands, namely the assembly of the shiny new metal two-wheel carriage for her shiny new poop bucket.

A familiar contrivance to those of an equestrian bent whose daily efforts hope to slow a stable’s inevitable descent into an animal waste collection facility, the design of these things has progressed over the centuries from a wonderfully functional large wicker basket with no moving parts to today’s unlikely design: An impressively unnecessary array of powder-coated metal struts and braces, two wheels wobbling on their axles against their cotter pins, an ergonomically-angled dolly-style handle padded with foam rubber to absorb and help spread microorganisms, automatic climate control and gold-plated license plate frames. The actual bucket, for its part, is a large removable heavy-duty plastic affair which will be getting assimilated into the planet’s oceanic life or geologic substrate for millennia after humanity is dead and gone.

Most males know the urge to prove their worth by doing something for their beloved for which the male psyche is naturally wired (as opposed to, say, communication). And those of us who work excessive hours in the digital world understand the human need of returning to analog endeavors once in awhile. It’s hard to name a more analog area of human endeavor than anything that might concern a poop bucket.

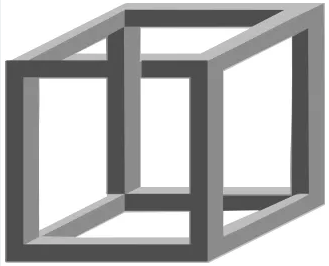

Standing in the front yard with the parts heaped at my feet like so much pot-metal spaghetti, I looked down at a badly wrinkled and blurred sheet of instructions in my hand: A single image of the final thing, drawn so poorly it had to be an act of sarcasm, rendered all the more indecipherable by the manufacturer’s having either printed a faxed image, or somehow gotten their hands on a cold war-era mimeograph machine to print the thing. Looking at the picture, it was impossible to tell what tubes were on top of or under, or in front of or behind other tubes, although through a careful codebreaking process of the verbal printed instructions, one could more or less arrive at the most likely concept.

“Are you sure?” Roni asked, no doubt just an innocent offer to handle a task that she thought might burden my day, but a question that nonetheless registered to my ears as “Are you sure you’re competent enough?”

“Yes m’Love, please let me handle it.”

Having been involved for a year in the mid-to-late nineties with the assembly, and very occasionally the designs, of things like computerized impact-testing gear, explosive squib testing apparatuses, electromagnetic levitation devices and laser interferometer sending / receiving modules–most of which was created at the level of things built by NASA and way over my head, but in the service of whose creation I nonetheless learned how things go together at the hands of mechanical geniuses–I’ve since been imbued with an appreciation of designs that are well-conceived and drawn, and not one bit more involved than absolutely necessary.

By the same token, I have an abiding and healthy contempt for the type of tragic comedy I now encountered. To my credit, I welcomed the entertainment value of what surely lay ahead.

“Game on”, I thought. “Joo VEEL be made to BEHAFE!” I said aloud.

My darling Roni was still hovering, so I added “Seriously m’Love, you said you need to get some rest, so go inside and get some rest. Lemme do this.” She proceeded to pull weeds nearby. My wife is no fool.

In the world of competent mechanical design, things are commonly done with fabrication tolerances of plus or minus one thousandth of an inch. More comfortably relaxed designs, for parts where things don’t really matter, might widen tolerances to plus or minus ten thousandths. In aerospace, sometimes things have to be within one micron.

The mechanical design of this thing, such as it was, employed very thin-walled tubing. This was a good thing, because it allowed for quality control specs of plus or minus a quarter mile, the components having been bent to vague angles and crimped to arbitrary degrees at the bore for each screw. It was hard not to visualize the process as having taken place behind a thatch hut with a pair of pliers held by someone dressed in a loincloth and assisted by his dog, a large wicker basket looking on from nearby and chuckling.

Still, I was unfazed and resolute. “Pity the poor thing”, I thought. “‘Tis no match for my codebreaking and puzzle-solving skills, nor my dogged stubbornness. It shall be assembled in short order, and in good form.”

I’ve dealt with this level of design and manufacture before: One gets the holes into the same area code then pulls things together, bending the frame pieces into their intended shape by carefully tightening the chinesium screws while internally chanting the universal assembler’s mantra: “Please don’t strip please don’t strip please don’t strip”.

Amidst a progressively growing assortment of tools and much creative profanity, engaging all of my limbs in what can only be described as a prolonged game of Twister with metal frame pieces, I was able to achieve the capture of those various unwieldy shapes at their various unlikely angles, then somehow maintain them while installing the fasteners.

At long last, while starting to slowly straighten up to stand majestically erect on the battlefield, knee-deep in a chaos of detritus and tools, not even bleeding and having triumphantly bent physics to my will in the name of all that is right in the universe, I was beholding the fruits of my labor and anticipating the presentation to the world of the completed conveyance, when Roni wandered up.

She took the thing in at a glance, immediately pointed and said, “Hey, that piece is on backwards!”

Damn.

No Comments